Why did a building on Waiheke Island that cost $54,000 in 2001 cost $1,000,000 in 2023?

Home price jumps 20X while income rises 4.5X… Why?

In March 2001, a property on Waiheke Island sold for $54,000 when median household income was $27,000. In May 2023, the same property sold for $1 million when the median household income was $120,000. This is the face of the affordable housing crisis. In 2001, beneficiary solo mums were encouraged by MSD to move to Waiheke so they could buy a home on the housing supplement. Two decades later, workers sleep in vans. Children born and raised on Waiheke must leave after school because they cannot afford to live on the island. Pensioners live on canned beans, impoverished by rising rents, yet they can’t afford the cost to move off island unless they walk away from their furniture and leave on the Gold-Card ferry only with a suitcase. What happened to Waiheke and throughout New Zealand to bring about these shocking circumstances?

The Old Guard Sacked: It began with a shift in council personnel. Older town and country planners, trained as civil engineers, saw their role as ensuring housing kept pace with population growth. For each new family—by birth or immigration—their job was to plan development and consent for one new home. Subdivision costs were low; councils funded infrastructure upgrades on bonds, knowing they’d recover the cost when rural land was rezoned into rate-rich building lots.

Restricted Land Supply: When the RMA came into force, universities gradually shifted to training students in environmental planning. These new planners replaced the civil engineers and brought an ethos that greenfield development was bad. They began writing rules that resisted maintaining a supply of developable land in line with population growth. As a result, land prices began to rise as demand outpaced supply.

Fees as Council Funding: This was made worse as councils, facing ratepayer resistance, turned to a user-pays model. Fees, fines, and contributions became essential to their budgets. Planning and Building Departments became self-funded, meaning to meet their budget they had to generate the revenue. As a monopoly this created a conflict of interest

Intentional Complex Consenting: A consent that might have cost $150 in 2001—often prepared by the landowner with help from a duty planner—now required expensive private consultants – some of whom wrote their district plans while working for the council, and then leaving to open consultancies to make applications to navigate this intentional red tape. By 2023, even minor errors could pause the process while costs continued to climb. Those naïve individuals who asked the council if they needed consent for a $60,000 mobile home found consent costs rising to $40,000 with no end in sight. Consenting had become a license to print money for Councils.

Cost of Building: In 1991, Parliament approved a new building act that permitted use of untreated radiata pine sap wood that had to remain completely dry or it would rot. Further, they allowed “Mediterranean” design that leaked, thus giving NZ the rotting house syndrome. This was caused by bad governance listening to powerful lobbies in the building material industry. Then, a decade later when these almost new buildings were rotting, a new Building Act was approved, ostensibly to prevent rotting buildings, but in fact created government protection for vested interests. The price of labour, approved building materials and the necessity of highly prescriptive building plans saw construction costs skyrocket.

“Regulators hear from suits paid to lobby. Low income people are just trying to get by— so they never connect.”

Cost of Building Consents: As with resource consents, fees, fines and contributions became an important part of the council’s revenue budgets. Initially this was driven by the court system finding councils were jointly and severally liable for the rotting buildings. In law, joint and several liability makes all parties in a suit responsible for damages up to the entire amount awarded. That is, if one party is unable to pay, the others named must pay more than their share. All the private sector parties went into liquidation, leaving the council holding the bag. This was a failing of Parliament that should have held itself liable since it approved the Building Act 2004.

The Perfect Storm: All of these contributors to the affordable housing crisis are the failing of central and local government. New Zealand has a structural weakness in that elected officials hear from vested interest and make policy that benefits their pecuniary interest. The ordinary person who pays the bills at the end – or become hidden homeless if they can’t has no voice.

There is an immediate, interim answer

Lowering the cost of new buildings will take decades, if ever possible. But in the short term there is an answer that sidesteps the perfect storm of building legislation: Chattel Housing.

Chattel housing are homes not fixed to land – mobile homes and tiny homes on wheels. If the law was properly administered, they do not require building consents under the Building Act because they are not buildings under the law. In many case, they do not require resource consent because most district and unitary plans govern structures which are real property fixed to land.

Councils don’t know what to do with chattel housing because the laws and plans were written when buildings were affordable, thus few spoke to mobile homes. Today when buildings are unaffordable, mobile homes and tiny homes on wheels are able to be purchased or leased at prices affordable by everyone, including pensioners, beneficiaries and recent school leavers.

Because of this omission, an immediate, interim solution to affordable housing is very simple. All the Minister and Cabinet need to do is affirm the oldest principles of property law, that mobile homes are chattel not realty.

“It’s not about new legislation. It’s about abiding by long-standing law.”

Housing Minister and Cabinet: Adopt this resolution

Housing that is not fixed to land is chattel, not realty. Mobile homes and tiny homes on wheels that are not permanently affixed to land are therefore not buildings under the law. For clarity, the use of conventional caravan connections for water, wastewater, and electricity do not constitute fixing a mobile home to land. Nor do measures such as removing wheels, blocking the chassis, or attaching safety chains, cables, or bolts to secure the unit against wind or earthquakes—provided an unlicensed person can lawfully remove these connections without damage and reattach the wheels – within a day or less.

It’s not a loophole. Extensive regulation for mobile homes is not necessary. Unlike buildings, they can be here today, gone tomorrow. They do not permanently change the land like buildings do. As chattel, they are not part of the land. And because they must be moved on roads, they are very small – far less impact than buildings.

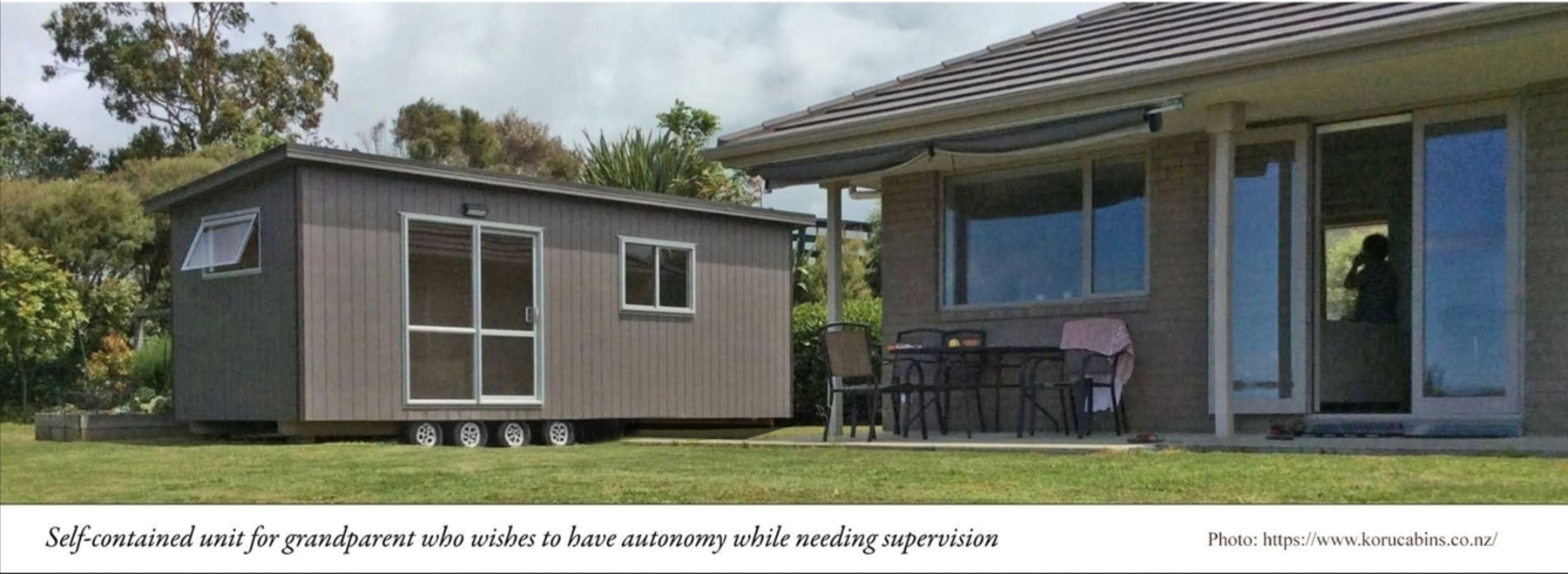

Government no longer reads law. This photo shows chattel housing. Mobile housing that is not fixed to land. "Not fixed to land" is a precise legal term that is fundamental to property law, and has been since 1066, almost unchanged. When councils, MBIE, MFE and MSD assert this chattel housing is a building, they are acting ultra vires (beyond their powers).

Government no longer reads law. This photo shows chattel housing. Mobile housing that is not fixed to land. "Not fixed to land" is a precise legal term that is fundamental to property law, and has been since 1066, almost unchanged. When councils, MBIE, MFE and MSD assert this chattel housing is a building, they are acting ultra vires (beyond their powers).

Cabinet to clarify that mobile homes and tiny homes on wheels are chattel housing not buildings and instruct councils, MBIE, MFE and MSD that mobile homes should be part of the portfolio of interim affordable housing not obstructed by district plan rules or Building Act rules intended for buildings (structures).

Cabinet to clarify that mobile homes and tiny homes on wheels are chattel housing not buildings and instruct councils, MBIE, MFE and MSD that mobile homes should be part of the portfolio of interim affordable housing not obstructed by district plan rules or Building Act rules intended for buildings (structures).